Listen to the audio blog

Medical disclaimer: This article is for education only and is not medical advice. Always consult your clinician for personal guidance.

If you’re an endurance athlete, you’ve probably had this moment: your fitness is undeniable—resting heart rate is low, VO₂ is high, your training log looks like a work of art—and then a blood test shows LDL (“bad cholesterol”) is higher than expected.

That can feel unfair. It can also trigger a very specific fear:

“If I take a statin, will I lose performance?”

This post is a practical, athlete-minded guide to lowering cholesterol—especially LDL and ApoB—while protecting the thing you care about most: how you feel and perform in training and racing.

Quick note: this is educational, not personal medical advice. Lipid decisions depend a lot on your age, family history, blood pressure, diabetes status, calcium score, prior heart events, and more. Use this to have a sharper conversation with your clinician.

1) The one idea that makes everything else make sense: lowering LDL lowers risk

There’s a reason statins are a first-line tool worldwide: lowering LDL cholesterol reduces the risk of major vascular events (heart attack, stroke, revascularization). Large meta-analyses from the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration show that reducing LDL meaningfully reduces cardiovascular events, even in people who are not “high risk.” [1]

Even more importantly for athletes who want options: the relationship is not “magic statins.” It’s mostly about LDL lowering itself, regardless of how you do it (statins or other LDL-receptor–based therapies). A JAMA meta-analysis found that each ~1 mmol/L (38.7 mg/dL) reduction in LDL is associated with a similar relative reduction in major vascular events across statins and several nonstatin LDL-lowering approaches. [2]

Translation: If you truly need your LDL/ApoB lower, you and your clinician can choose from multiple strategies—and the goal is not just “take a statin,” it’s “achieve and maintain a safer LDL/ApoB level.”

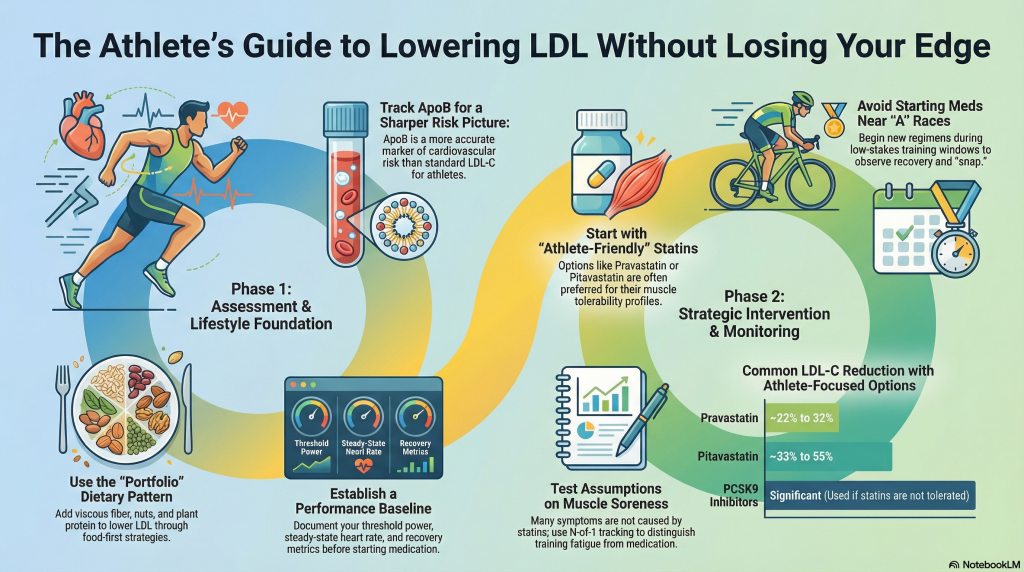

2) “Cholesterol” is too vague. Athletes should track ApoB (or at least non-HDL)

Most standard lipid panels emphasize LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides. Helpful—but athletes (especially endurance athletes) can benefit from one extra marker:

- ApoB is a proxy for the number of atherogenic particles (LDL particles and similar). It’s often a clearer measure of cholesterol-driven risk than LDL-C alone, especially when LDL-C and particle number don’t match. A major physiology-focused review explains why ApoB is often the more accurate marker of risk. [3]

If ApoB isn’t available, non-HDL cholesterol is a decent “second-best” option (it captures all atherogenic cholesterol).

Athlete takeaway: ask your clinician whether ApoB (and sometimes lipoprotein(a)) should be part of your routine monitoring—especially if you’re lean, highly trained, and still seeing high LDL.

3) The athlete’s foundation: diet still matters, even if you train a lot

Training improves many cardiometabolic markers, but it does not guarantee optimal LDL—especially if genetics are strong, or if your diet leans hard into saturated fat (common in some high-calorie endurance fueling patterns).

The American Heart Association’s dietary guidance focuses on overall patterns: emphasize vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, healthy proteins, and reduce saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars. [4] Their broader scientific guidance also reinforces building a dietary pattern that supports cardiovascular health rather than chasing a single “perfect macro ratio.” [5]

A highly effective “food-first” LDL tool: the Portfolio dietary pattern

The Portfolio diet combines several cholesterol-lowering foods (viscous/soluble fiber, plant proteins, nuts, and phytosterols). A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials found it leads to clinically meaningful improvements in LDL-C and other cardiometabolic risk factors. [6]

Practical way to use this as an athlete:

You don’t need to go fully plant-based. Many athletes do well simply by adding:

- A daily viscous fiber source (oats, barley, psyllium)

- Nuts most days

- More legumes/soy or plant-forward meals

- Keeping saturated fat in check (especially butter, coconut oil, high-fat dairy, fatty red meats)

4) When lifestyle isn’t enough (or risk is high): the athlete’s reality about statins

If you’re offered a statin, you’re usually in one of two buckets:

- Primary prevention: you haven’t had a cardiovascular event, but your LDL/ApoB (or overall risk) is high enough that medication is reasonable.

- Secondary prevention: you have known coronary disease or a prior event—risk is higher, and the benefits of lipid lowering are usually larger.

Athletes often accept the logic of prevention—but hesitate at the execution because of muscle fears.

That brings us to the question athletes actually care about:

Do statins reduce performance?

There’s no single perfect study in elite endurance athletes, but the best overall evidence is reassuring:

- The American College of Cardiology (ACC) has an athlete-focused review specifically addressing statins and performance. It notes that statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS) are more commonly reported in athletes and highly active people, but also emphasizes that evidence for reduced aerobic capacity is not definitive. [7]

- In the STOMP trial (a randomized, placebo-controlled study), high-dose atorvastatin increased muscle symptoms and creatine kinase (CK), but did not reduce muscle strength or exercise performance over 6 months in healthy participants. [8]

So why do athletes still worry? Because elite performance is sensitive. You don’t need a dramatic lab-measured decline to feel that something is off in training rhythm, recovery, or “snap.”

5) Muscle symptoms are real… but many are not caused by the statin

This matters because it changes how you troubleshoot.

A large individual-participant meta-analysis in The Lancet examined muscle symptoms in randomized statin trials and found that statins cause only a small excess of muscle symptoms versus placebo; many reported symptoms are not actually attributable to the statin. [9]

Even more “athlete-relevant,” there are n-of-1 trial designs—where people alternate statin and placebo in blinded fashion. A prominent BMJ series of randomized n-of-1 trials in people who believed they were statin-intolerant found that symptom intensity was similar during statin and placebo periods, consistent with a strong nocebo component for many individuals. [10]

What this means for athletes:

You should take symptoms seriously, but you should also test assumptions. In a hard training cycle, soreness happens. The question is whether the statin is adding a distinct, repeatable pattern.

6) The endurance-athlete nuance: extreme effort can magnify muscle damage signals

Here’s a piece athletes should know: even if statins don’t reduce VO₂max in a controlled study, they may change the muscle-damage response to very hard endurance events in some people.

A study of Boston Marathon runners found statin users had higher skeletal muscle injury markers (including CK isoenzymes) around the marathon compared with controls. [11]

This does not prove statins ruin endurance performance. But it supports a common real-world athlete experience:

some athletes feel “fine” day-to-day, but notice worse recovery cost after major efforts.

7) Choosing a statin like an athlete: start with strategy, not superstition

Clinicians often talk about statins by “intensity.” Athletes should also think in terms of:

- minimum effective dose

- tolerability

- consistency

- interaction profile (if you’re on multiple meds)

- how it fits your training calendar

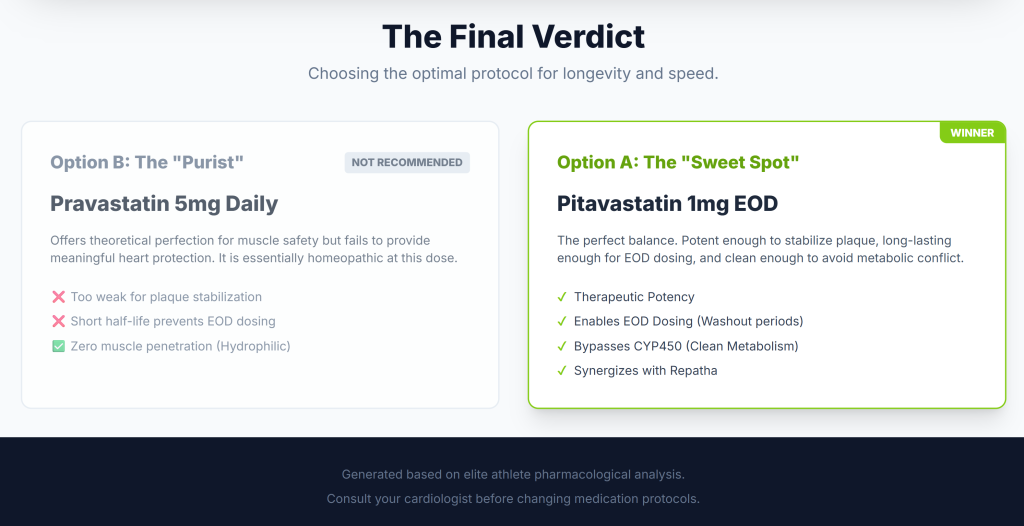

Pravastatin (often considered “athlete-friendly”)

Pravastatin is commonly used when muscle tolerability is a concern. In a Cochrane review, pravastatin reduced LDL-C in a dose-dependent manner (roughly ~22% to ~32% across common licensed doses). [12]

Athlete framing: pravastatin is a reasonable “start low and see” option, especially if your risk isn’t extreme and you’re highly concerned about muscle symptoms.

Pitavastatin (a potent option at low milligram doses)

Pitavastatin is less commonly discussed in casual athlete circles, but it has a notable feature: it’s potent per milligram. A Cochrane review found pitavastatin 1–16 mg/day lowered LDL-C roughly ~33% to ~55% depending on dose. [13]

Head-to-head data in older adults show pitavastatin (1–4 mg) produced greater LDL lowering than pravastatin (10–40 mg) over 12 weeks. [14]

Athlete framing: pitavastatin can be a “small pill, meaningful LDL effect” option—useful when you want LDL/ApoB down without escalating to large statin doses. (Whether that translates into better tolerability is individual.)

8) “Micro-dosing” and alternate-day dosing: a real-world tool, but don’t overpromise it

Some athletes do best on very low doses or non-daily schedules—especially if they’re symptom-prone.

Alternate-day dosing has been discussed in clinical literature as a way to maintain LDL improvements while improving tolerability for some patients. The American College of Cardiology reviewed alternate-day dosing and notes that LDL lowering can remain meaningful in many cases, but that outcome-level evidence is less definitive and the approach is often used pragmatically. [15] A review in The American Journal of Medicine similarly summarized that LDL reduction with alternate-day dosing can be close to daily dosing in some studies. [15]

Athlete approach:

If you and your clinician use alternate-day dosing, treat it like training experimentation:

- measure LDL/ApoB response

- track symptoms and performance markers

- adjust with data, not vibes

9) What about PCSK9 inhibitors (like Repatha/evolocumab)? Big LDL reductions, proven outcomes

PCSK9 inhibitors can be game-changers for athletes who:

- have familial hypercholesterolemia or very high LDL/ApoB

- have established coronary disease and need very low LDL

- can’t tolerate sufficient statin therapy

The FOURIER trial (NEJM) showed that adding evolocumab to statin therapy lowered LDL dramatically and reduced cardiovascular events compared with placebo. [16]

One subtle—but important—point for athletes who assume “lower LDL = less inflammation”:

In a Circulation analysis from FOURIER, baseline hsCRP stratification showed that hsCRP levels were not altered by evolocumab, yet cardiovascular benefit was consistent across inflammation strata. [17]

Athlete takeaway: PCSK9 inhibitors are powerful LDL tools with outcomes data. They may not substitute for every statin “pleiotropic” theory, but they do what matters most: lower LDL a lot, and reduce events.

10) An athlete-friendly cholesterol-lowering playbook (put this on one page)

Here’s a clean, practical regimen to discuss with your clinician. Not a prescription—think of it as a framework.

Step 1: Get the right baseline numbers

Ask for:

- LDL-C, non-HDL-C, triglycerides, HDL-C

- ApoB (if possible)

- Consider lipoprotein(a) if family history or early disease

- If you’re starting medication and you’re an intense trainer, consider documenting a baseline CK (interpretation is athlete-specific).

Step 2: Do a 6–12 week “LDL diet block” like you’d do a training block

Use AHA-style dietary patterns as your base. [4], [5]

Layer in Portfolio components if LDL is stubborn. [6]

Step 3: If meds are indicated, start with the minimum effective plan

Common athlete-minded strategies clinicians may consider:

- Low-dose daily statin

- Low-dose statin + nonstatin add-on (to avoid high statin doses)

- Alternate-day statin if symptoms are an issue (with lab follow-up) [15]

Step 4: Don’t start a new statin the week of your A race

Start medication in a lower-stakes training window when you can observe recovery patterns.

Step 5: Track performance like an experiment

Pick 2–3 stable markers:

- a threshold session you repeat

- a steady-state HR/pace or HR/power relationship

- recovery metrics (sleep, soreness, HRV if you use it consistently)

Step 6: Know the red flags (rare, but serious)

Stop and get medical help urgently if you have:

- profound weakness

- dark urine

- severe muscle pain with systemic symptoms (fever, malaise)

Bottom line for athletes

- LDL lowering matters for long-term cardiovascular risk, and the benefit scales with the amount of LDL reduction. [1], [2]

- Statins do not reliably reduce measured performance in controlled trials, but athletes may be more likely to notice symptoms or recovery changes, and extreme endurance events can amplify muscle-damage signals in some statin users. [7], [8], [11]

- If you need medication, you and your clinician can often design an approach that protects both your arteries and your athletic engine—using dose selection, monitoring, and (when appropriate) combination therapy like PCSK9 inhibitors. [14], [16]

Endnotes

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. The Lancet (2012). (The Lancet)

- Silverman MG, et al. Association Between Lowering LDL-C and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Among Different Therapeutic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA (meta-regression of 49 trials). (JAMA Network)

- Hegele RA, Sniderman AD. Physiological Bases for the Superiority of Apolipoprotein B vs LDL-C and non-HDL-C in risk assessment (incl. reference to 2019 ESC/EAS position on apoB). Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA). (American Heart Association Journals)

- American Heart Association. Diet and Lifestyle Recommendations (heart-healthy eating pattern guidance). (www.heart.org)

- American College of Cardiology summary of AHA Scientific Statement. 2021 AHA Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: Key points. (American College of Cardiology)

- Chiavaroli L, et al. Portfolio Dietary Pattern and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Controlled Trials. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases (2018). (ScienceDirect)

- Chiampas K, et al. American College of Cardiology. I Am an Athlete: Will This Statin Affect My Performance? (2024). (American College of Cardiology)

- Parker BA, et al. Effect of Statins on Skeletal Muscle Function and Performance (STOMP study). Circulation (AHA). (American Heart Association Journals)

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Effect of statin therapy on muscle symptoms: an individual participant data meta-analysis of large-scale, randomised, double-blind trials. The Lancet (2022). (The Lancet)

- Wood FA, et al. Statin treatment and muscle symptoms: series of randomised, placebo controlled n-of-1 trials. The BMJ (2021). (BMJ)

- Effect of Statins on Creatine Kinase Levels Before and After a Marathon Race (Boston Marathon cohort). American Journal of Cardiology (2011). (AJC Online)

- Cochrane. Pravastatin for lowering lipids (dose-response effects on LDL-C). (Cochrane)

- Cochrane. Pitavastatin for lowering lipids (dose-response effects on LDL-C). (Cochrane)

- Stender S, et al. Pitavastatin shows greater lipid-lowering efficacy over 12 weeks than pravastatin in elderly patients with hypercholesterolaemia/mixed dyslipidaemia. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology (2013). (OUP Academic)

- American College of Cardiology. Alternate-Day Dosing With Statins (review and points to remember), plus supporting review in The American Journal of Medicine. (American College of Cardiology)

- Sabatine MS, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease (FOURIER). New England Journal of Medicine (2017). (New England Journal of Medicine)

- Bohula EA, et al. Inflammatory and Cholesterol Risk in the FOURIER Trial (hsCRP stratification; hsCRP not altered by evolocumab; benefit consistent across strata). Circulation (Europe PMC record). (Europe PMC)

AI Use Notice: Portions of this article were drafted with the assistance of AI tools. The author reviewed and edited the content, verified sources where applicable, and is responsible for the final version. This content is for educational purposes and is not medical advice.