Listen to the audio blog

Medical disclaimer: This article is for education only and is not medical advice. Always consult your clinician for personal guidance.

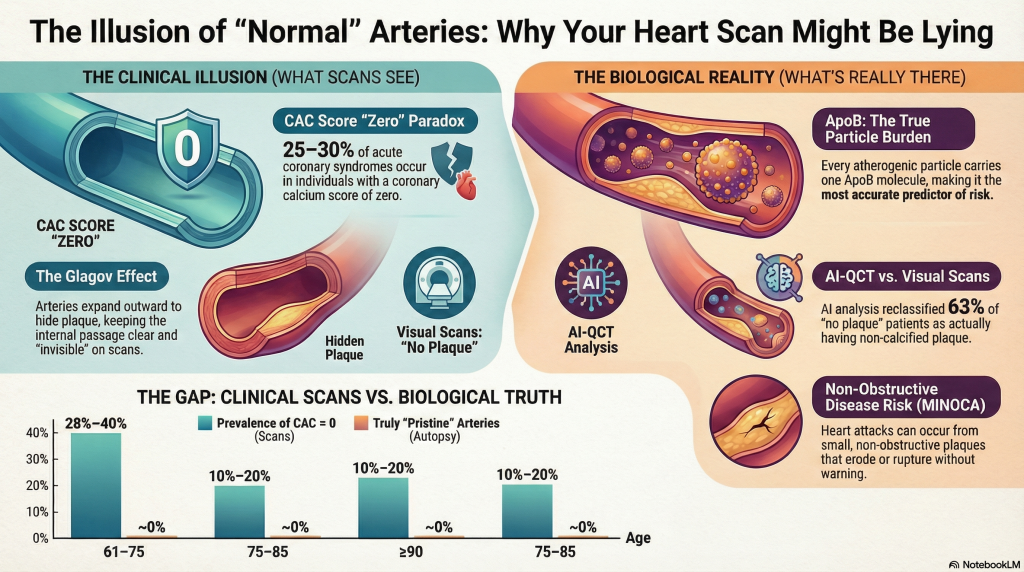

The clinical assertion that individuals maintaining markedly elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and apolipoprotein B (ApoB) can possess anatomically “normal” coronary arteries at age 60 represents a diagnostic paradox. This phenomenon often hinges on the resolution of the imaging tool used. While contemporary tools like the Coronary Artery Calcium (CAC) score and standard visual Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography (CCTA) provide a high-resolution window into the arterial wall, they exist in tension with pathological evidence which suggests that atherosclerosis is a nearly universal condition of human aging, and clinical data showing that heart attacks can occur even in the absence of significant anatomical blockages [1].

The Causal Framework of Lipoprotein-Driven Atherogenesis

The consensus establishes that prolonged exposure to ApoB-containing lipoproteins is the primary driver of atherosclerotic plaque [2]. Each atherogenic particle—including LDL, VLDL, and IDL—carries a single molecule of ApoB, making it a direct measure of the total number of circulating particles that can penetrate the arterial wall [2]. The probability of a particle becoming trapped in the subendothelial space is a function of both particle concentration and the duration of exposure, often quantified as “ApoB-years” [2].

While LDL-C measures the mass of cholesterol, ApoB reflects the particle burden [3]. In cases of discordance—where ApoB is high but LDL-C is relatively lower—ApoB remains the more accurate predictor of future myocardial infarction (MI) and clinical events [4].

Lipoprotein Metrics

| Lipoprotein Metric | Definition and Pathological Role | Association with Plaque Burden |

| Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) | The mass of cholesterol contained within LDL particles | Causal, but may be discordant with particle count [3] |

| Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) | A structural protein; one exists on every atherogenic particle | Strongest predictor of risk; reflects true particle burden [3] |

| Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] | An LDL-like particle with an additional protein [apo(a)] | Independent risk factor; promotes calcification and thrombosis [5] |

Forensic vs. Clinical Reality: The “Pristine” Artery Illusion

The claim that an individual can reach age 60 without “arterial damage” is often a result of clinical imaging failing to detect microscopic disease. Forensic autopsy studies, including the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) and the Bogalusa Heart Study, demonstrate that microscopic fatty streaks—the earliest macroscopic evidence of atherosclerosis—are present in nearly all adolescents examined [6].

By the sixth decade of life, pathologically pristine coronary arteries are virtually absent in Westernized populations. Diffuse intimal thickening and lipid deposition become ubiquitous by midlife, and contemporary autopsy cohorts report coronary atherosclerosis in nearly all adults by the fourth decade [6].

The Glagov Effect: How Arteries Hide Plaque Burden

A critical contributor to “normal” coronary imaging is the Glagov phenomenon, or compensatory outward remodeling [7]. As plaque accumulates within the arterial wall, the vessel expands externally to preserve luminal diameter and maintain blood flow [7]. Hemodynamically significant luminal narrowing is typically delayed until plaque burden exceeds approximately 40% of the internal elastic lamina area [7].

Because standard invasive angiography and conventional visual CCTA focus primarily on the lumen, substantial plaque burden may exist within the vessel wall while remaining angiographically invisible [7]. These concealed plaques are often lipid-rich and biologically active, rendering them prone to erosion or rupture capable of precipitating MI even in the absence of pre-existing stenosis [1].

AI-QCT (Cleerly) vs. Standard Visual Interpretation

Artificial Intelligence–Quantitative Computed Tomography (AI-QCT) platforms, such as Cleerly, have demonstrated that standard visual interpretation of CCTA systematically underestimates plaque burden [8]. By enabling volumetric plaque quantification and compositional analysis, AI-QCT achieves accuracy approaching invasive intravascular ultrasound [8].

In a cohort of approximately 750 patients, AI-QCT analysis led to diagnostic modification in 39% of cases, while the number of patients classified as having “no plaque” fell from 159 to 58 following quantitative assessment [8]. These findings confirm that visually “normal” coronary CT angiograms frequently harbor clinically relevant non-calcified plaque.

Coronary Artery Calcium Score and Myocardial Infarction Risk

Coronary Artery Calcium scoring is a powerful population-level risk stratification tool, but its relationship with individual myocardial infarction risk is probabilistic rather than absolute. Large prospective cohorts, including the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), demonstrate a strong graded association between CAC burden and future coronary heart disease events, with markedly elevated risk observed at scores ≥300 [11].

However, a CAC score of zero does not confer immunity from MI. Although short-term event rates are low, non-calcified, lipid-rich plaques—particularly in individuals with elevated ApoB—remain capable of rupture or erosion [12]. Approximately 25–30% of acute coronary syndromes occur in individuals with absent or minimal coronary calcification at baseline, reflecting the temporal disconnect between plaque formation, calcification, and plaque instability [12]. Calcification is increasingly recognized as a marker of plaque chronicity and healing rather than vulnerability, whereas non-calcified plaque burden correlates more closely with near-term risk.

Thus, CAC scoring is best interpreted as a measure of cumulative plaque burden and long-term risk rather than as a detector of biologically active atherosclerosis. In high–ApoB individuals, a CAC score of zero more likely reflects delayed disease expression than true disease absence.

MI Risk With “Near-Zero” Plaque Burden: The MINOCA Syndrome

Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries (MINOCA) accounts for approximately 5–15% of all acute myocardial infarctions [1]. Even small, non-obstructive plaques may undergo endothelial erosion, triggering localized thrombosis without angiographically visible obstruction [9].

Importantly, ApoB remains a strong independent predictor of MI risk even among individuals without obstructive coronary disease, as demonstrated in large population cohorts and randomized lipid-lowering trials [4].

Longitudinal Data: Prevalence of Zero Plaque From 60 to 100 Years

Despite near-universal atherosclerosis on pathological examination, clinical imaging registries identify a subset of individuals who maintain zero coronary calcification into advanced age [10].

| Age Group (Years) | Prevalence of CAC = 0 (Clinical Imaging) | Likelihood of Truly “Pristine” Arteries (Autopsy) |

| 61–75 | 28%–40% | ~0% |

| 75–85 | 10%–20% | ~0% |

| ≥90 | ~5% | ~0% |

In the oldest old, a so-called “cholesterol paradox” has been observed, wherein higher LDL-C levels (≥130 mg/dL) are sometimes associated with longer survival, likely reflecting survival bias or age-dependent protective roles of cholesterol in immune function and cellular repair [10].

Conclusion

The evidence confirms that while elevated ApoB and LDL are primary causal agents of atherosclerosis, a meaningful minority of individuals may reach age 60 with no visible plaque on standard clinical imaging. In most cases, this apparent normality reflects the limits of imaging resolution and compensatory arterial remodeling rather than true absence of disease. Advanced AI-QCT analysis demonstrates that many presumed “escapees” harbor substantial non-calcified plaque burden. Moreover, MI risk—including MINOCA—remains elevated in the presence of high ApoB even without obstructive disease. For individuals with rigorously confirmed minimal plaque burden at age 60, elevated ApoB may represent latent rather than expressed risk, supporting a personalized rather than universally aggressive preventive strategy.

References

- Tamis-Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, et al. Contemporary diagnosis and management of patients with myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2019;139(18):e891–e908. PMID: 30913893.

- Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(32):2459–2472. PMID: 28444290.

- Sniderman AD, Thanassoulis G, Williams K, Pencina M. Apolipoprotein B particles and cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiology. 2019;4(12):1287–1295. PMID: 31714941.

- Marston NA, Giugliano RP, Im K, et al. Association between apolipoprotein B and residual cardiovascular risk after statin therapy. JAMA Cardiology. 2022;7(3):250–256. PMID: 35072737.

- Tsimikas S. Lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;69(6):692–711. PMID: 28183512.

- Strong JP, Malcom GT, McMahan CA, et al. Prevalence and extent of atherosclerosis in adolescents and young adults. JAMA. 1999;281(8):727–735. PMID: 10052443.

- Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;316(22):1371–1375. PMID: 3574413.

- Nurmohamed NS, Dedic A, Stuijfzand WJ, et al. Impact of quantitative coronary CT angiography on diagnostic certainty and clinical management. European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging. 2024;25(6):857–866. PMID: 38422547.

- Agewall S, Beltrame JF, Reynolds HR, et al. ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(3):143–153. PMID: 28158518.

- Mortensen MB, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated LDL cholesterol and survival in older individuals. The Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1644–1652. PMID: 33271000.

- Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, et al. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(18):1860–1870. PMID: 17481445.

- Blaha MJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, Greenland P, et al. Role of coronary artery calcium score in the prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA Cardiology. 2018;3(2):122–130. PMID: 29297046.

AI Use Notice: Portions of this article were drafted with the assistance of AI tools. The author reviewed and edited the content, verified sources where applicable, and is responsible for the final version. This content is for educational purposes and is not medical advice.